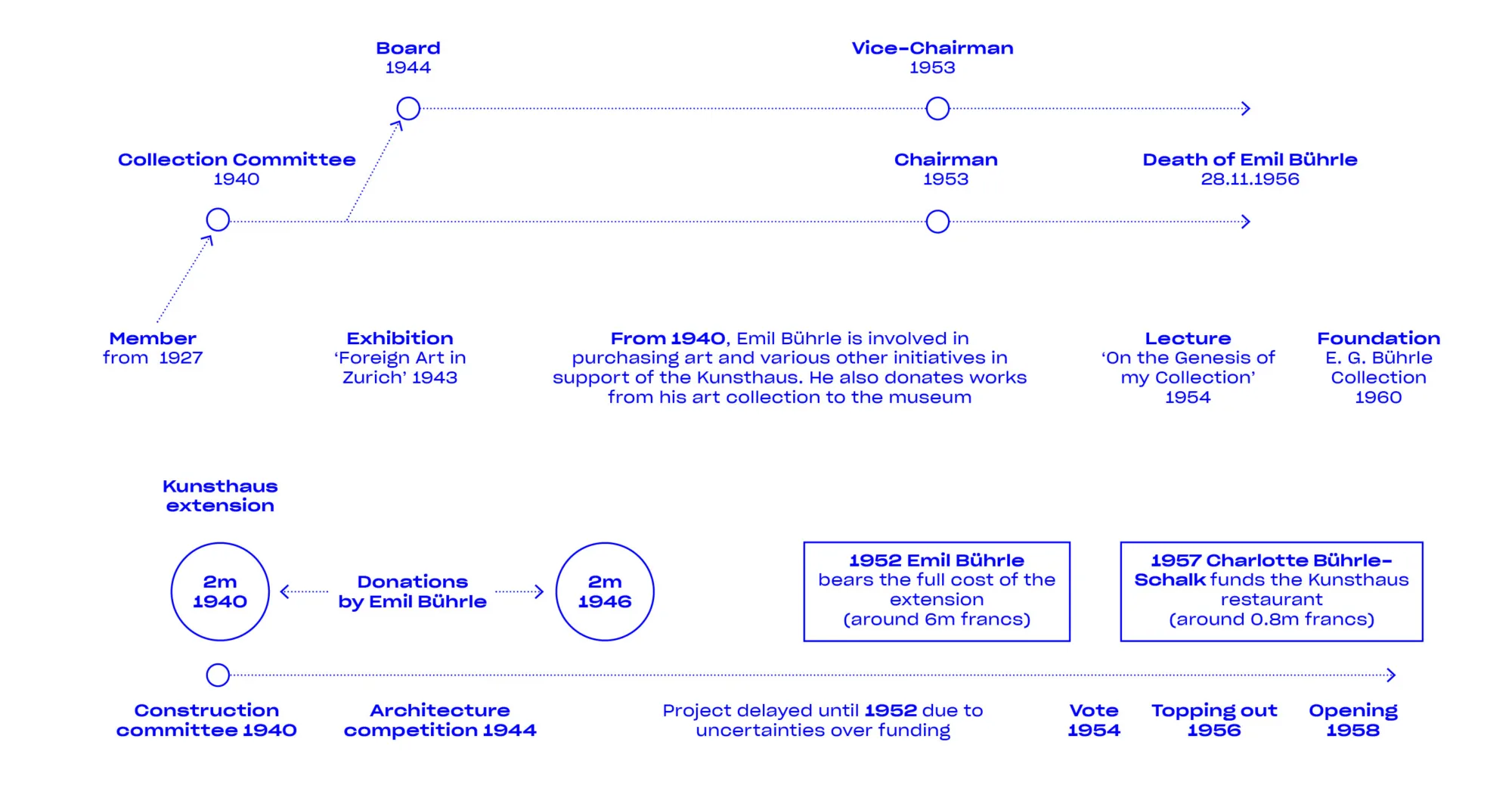

When he dies in 1956, Emil Bührle leaves no instructions concerning what is to be done with the works in his collection. In 1960, four years after his death, his widow Charlotte Bührle-Schalk and their children establish the Foundation E. G. Bührle Collection in Zurich. They transfer around a third of the collection’s holdings – 221 works out of a total of 633 – to the foundation. The remainder stays in private ownership. Their selection ensures that the structure and completeness of the collection that Emil Bührle had sought to achieve is preserved in the Foundation, which is housed in the family villa at Zollikerstrasse 172 in Zurich. It is open to the public from April 1960 to the end of May 2015. Between 1961 and 2019, parts of the collection are shown in various museums in the US, Canada, the UK, France, Germany and Japan.

Following the events of May 1968 and the ‘Bührle affair’ of 1970, as a result of which Bührle’s son Dieter is found guilty of illegal arms trading with South Africa and Nigeria, the Zürcher Kunstgesellschaft distances itself from the Foundation E. G. Bührle Collection, a state of affairs that persists until the mid-1990s.

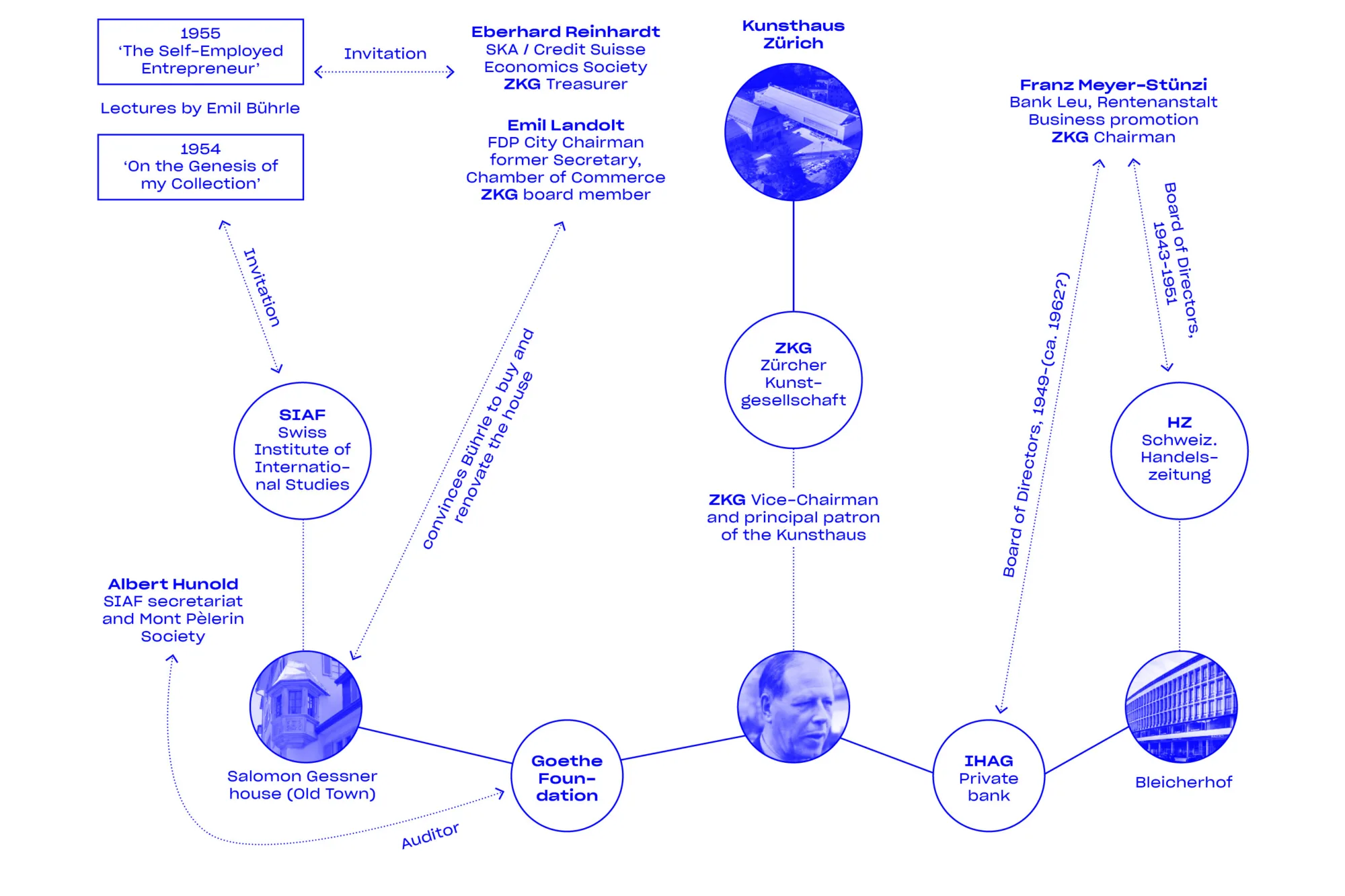

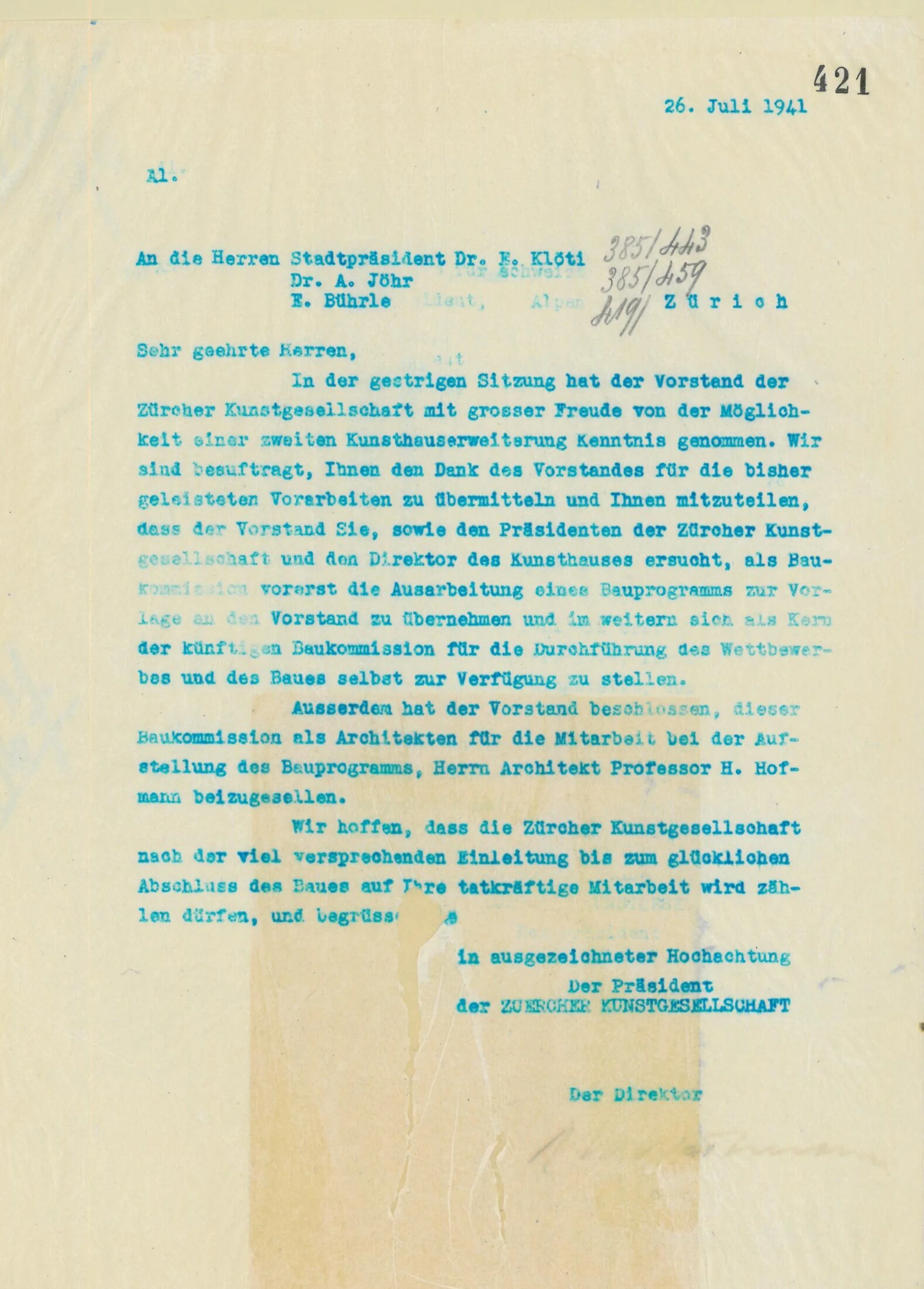

In 2005, the start of planning for a new extension to the Kunsthaus on the other side of Heimplatz leads to a rapprochement. Following initial discussions in the late 1990s, a preliminary agreement in principle between the Foundation E. G. Bührle Collection, the Kunstgesellschaft and the founding family is signed in 2006. It provides for the foundation’s collection to be transferred to the planned extension. This agreement is backed by Zurich’s City Parliament and the electorate in a vote held in 2012, with 53.9% voting in favour on a turnout of 36.5%. The extension designed by Sir David Chipperfield opens in 2021 with the Emil Bührle Collection on display inside it.

The transfer of the foundation’s collection to the Kunsthaus Zürich is heavily criticised, both during preparations and when it takes place. In their Schwarzbuch Bührle (Bührle Black Book), published in 2015, Guido Magnaguagno and Thomas Buomberger critically assess Bührle’s role in politics and society along with the associated topic of looted art. In 2016, the City and Canton of Zurich commission a team of researchers headed by the historian Matthieu Leimgruber to investigate the context of the Emil Bührle Collection. Its report is published in 2020, and highlights how well connected Bührle was in Switzerland and internationally, both as an arms manufacturer and as an art collector. In 2021, historian Erich Keller publishes a book entitled Das kontaminierte Museum (The Contaminated Museum). It examines local politicians’ activities to promote the city of Zurich, contemporary developments in dealing with looted art, and Switzerland’s culture of remembrance with regard to the Second World War, and combines them in an important contribution.

The move to the Kunsthaus has brought the foundation’s collection into the public spotlight. A heated debate rages in the media and among the public. Should the collection be displayed in a museum that receives public as well as private funding? Does it contain looted art or works whose provenance is unresolved? How could a neutral country such as Switzerland allow Bührle to sell weapons to the Nazis? Should all the works acquired by Bührle be removed from the public gaze because much of his wealth was accumulated through weapon sales to the Nazi state?

In response to the intense social, media and political controversy surrounding the public presentation of the Emil Bührle Collection in the extension, the City and Canton of Zurich and the Zürcher Kunstgesellschaft convene a round table headed by Felix Uhlmann. It appoints the historian Raphael Gross to review the research into the provenance of the works in the E.G. Bührle Collection. Its report is expected to be published in summer 2024.