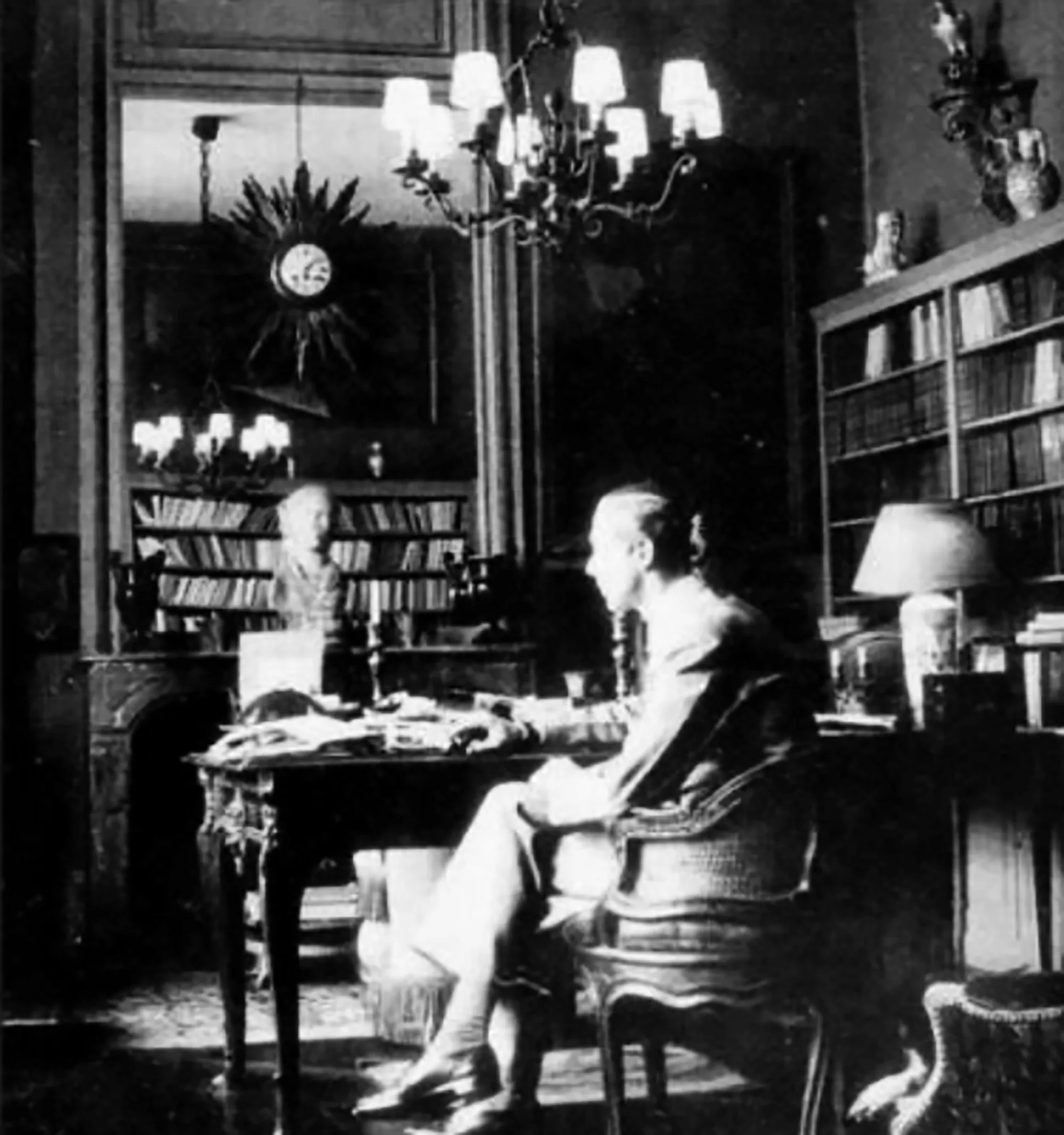

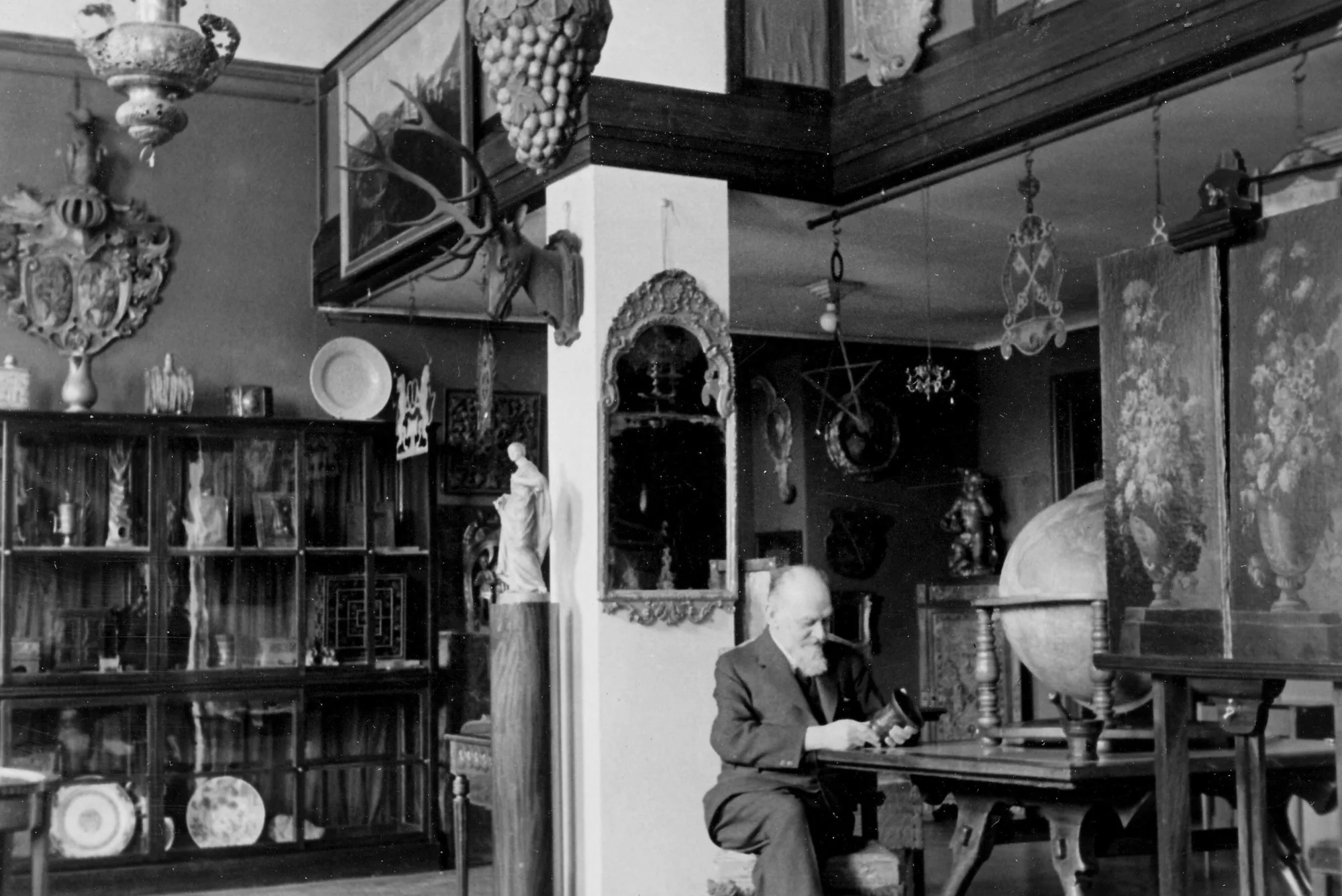

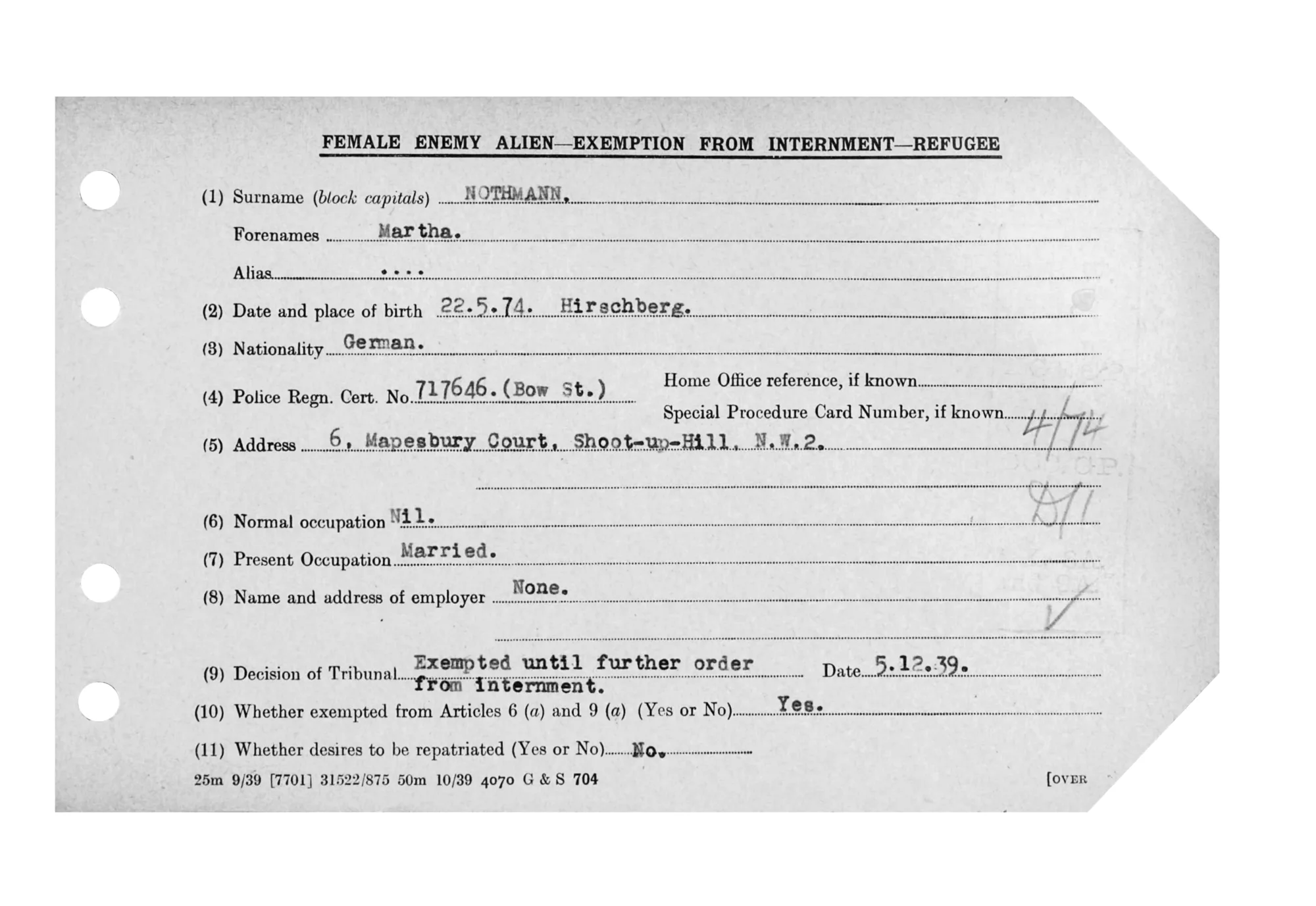

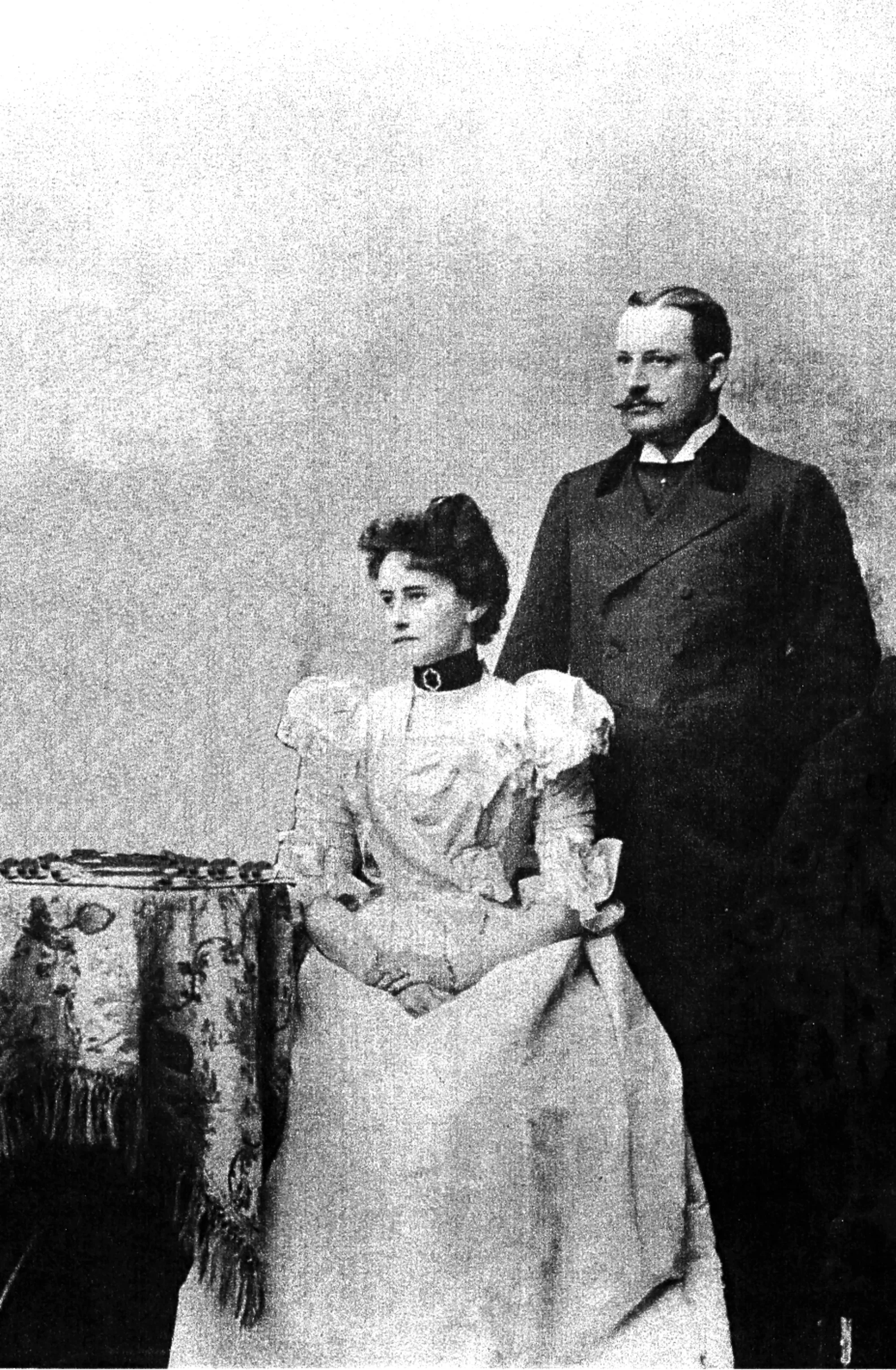

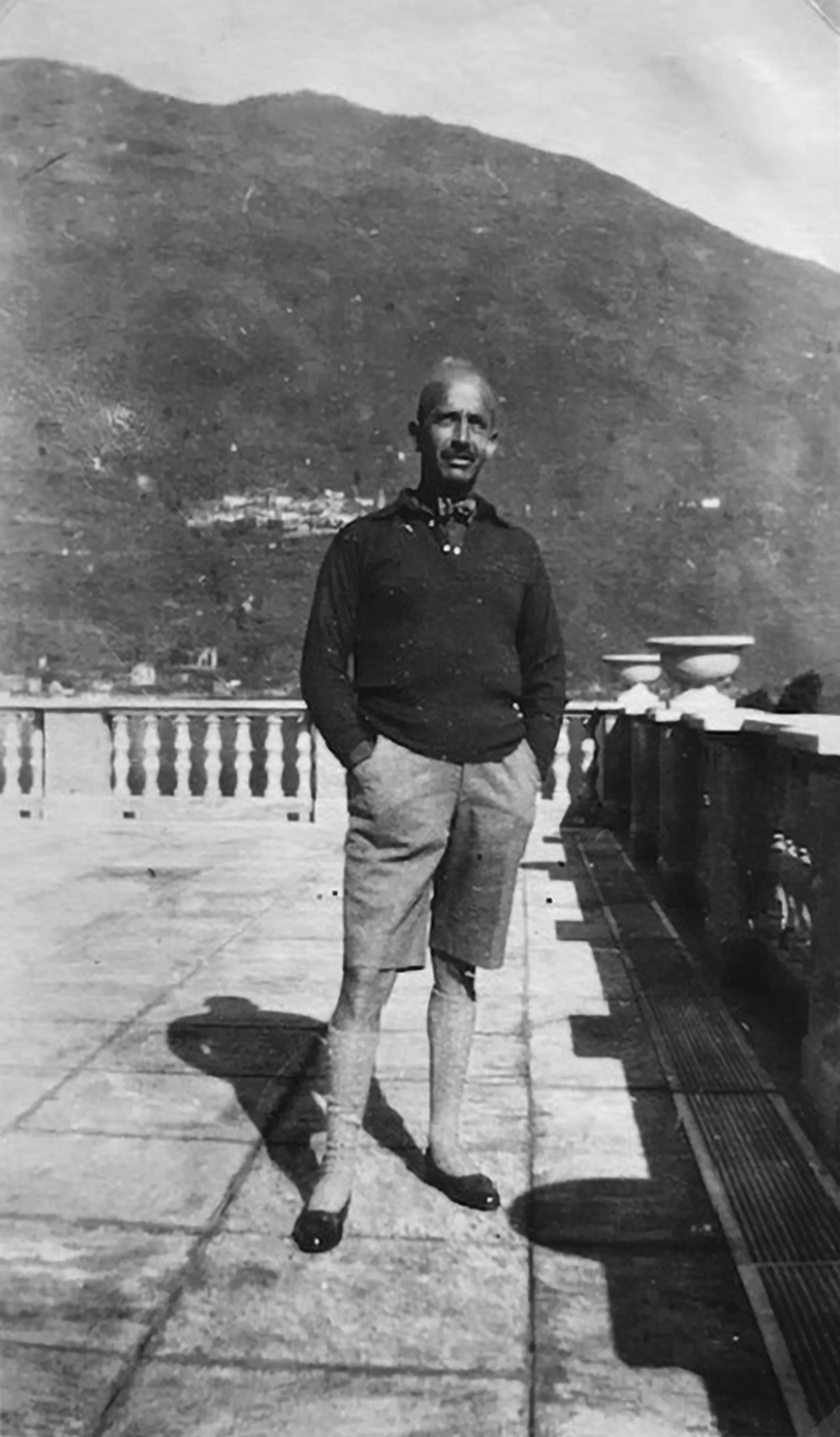

Moïse Lévi de Benzion (1873–1943) was an Egyptian Jewish real estate and department store owner. In Cairo, he headed the family company Grands Magasins Benzion, which was founded in 1857. He used part of his wealth to accumulate a collection of artworks as well as Asian and Egyptian antiquities. De Benzion owned a residence south of Paris. The Nazis persecuted him due to their antisemitic ideology. Under life-threatening circumstances, he succeeded in fleeing to La Roche-Canillac in the unoccupied zone of France, where he died in 1943.

De Benzion’s collection remained in his residence. The ‘Reichsleiter Rosenberg Taskforce (ERR)’, an organisation set up by the Nazi party to loot cultural property, plundered it in 1941. More than 1,200 works of art were seized. Camille Corot’s painting Sitting Monk, Reading and Alfred Sisley’s Summer at Bougival arrived in the Lucerne gallery of Theodor Fischer

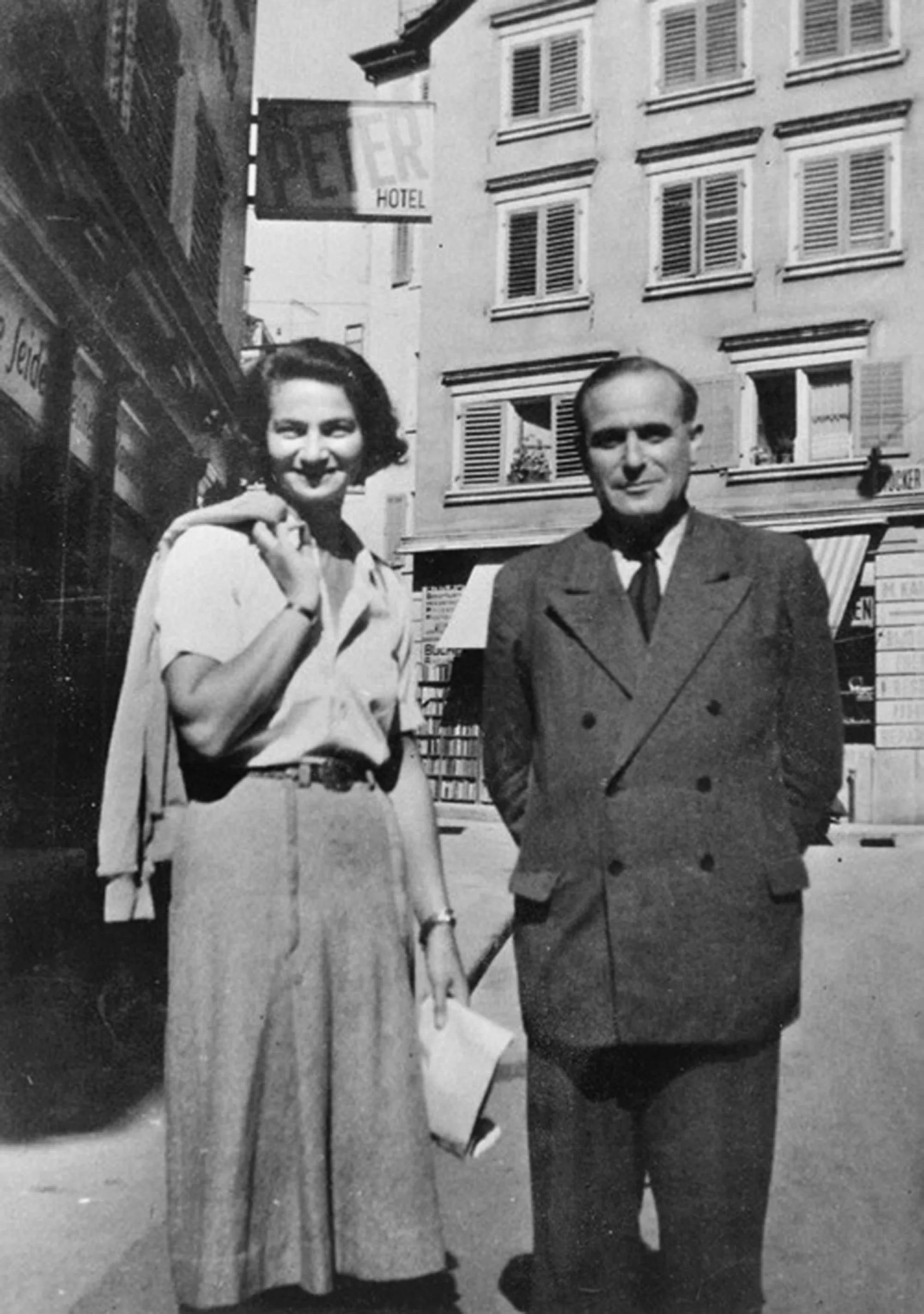

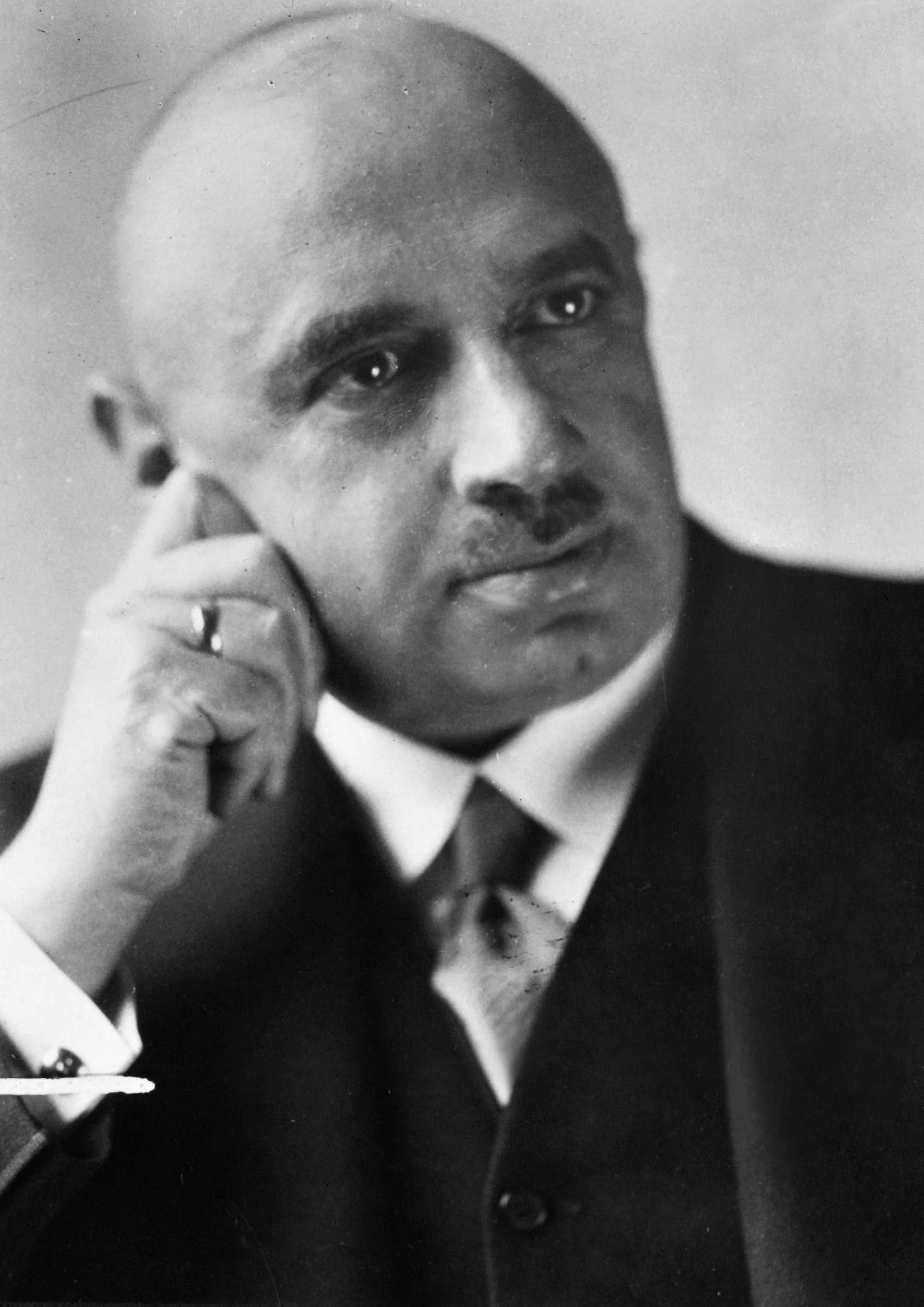

in 1941, who sold them on in 1942 to Emil Bührle. De Benzion’s heirs submitted a claim to the Chamber on Looted Assets of the Swiss Supreme Court after 1945, and won their case.

Bührle returned both paintings to the heirs in 1948, then reacquired them in 1950 after their value had been reassessed. In 1951, Bührle sued Fischer to recover the amount he had paid when first acquiring the works. The Federal Court accepted the claim. They decided that the purchase had been made by Bührle in good faith and that at the time of the purchase, he could not have known of the works’ unlawful provenance. The verdict remains controversial to this day, as Bührle may very well have known about the systematic looting of the Jewish collectors in 1942.